With Senegal (March) and South Africa (May) as some of Africa’s leading democracies going through elections in the first half of this year, this has triggered a reflection on elections in Africa in 2024 as it is a major elections year.

The Journey of Democracy in Africa.

Since the end of the advent of colonial rule, Africa has been on a steady path of democratic growth. The African Union (AU) has provided leadership in adopting a legal and policy framework within which democratisation need to happen as evidenced by the adoption of such pieces of instruments as the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights (ACHPR), the AU Constitutive Act, the African Charter on Democracy Elections and Governance (ACDEG) as well as declarations and standards governing democratic elections. This overall legal and policy framework in Africa recognises that the authority to govern is derived from the will of the people exercised through genuine free and fair elections that are held periodically. With these standards, the AU has also shifted from the principle of non-interference in the domestic affairs of the state, to adopt the principle of non-indifference which recognises that sovereignty comes with the responsibility to protect people’s rights under the state.

Elections, Coups and Governance

In this context elections in Africa are seen as a major vehicle of democratisation. This is evidenced by regular and generally chronologically compliant elections that are held as a method of choosing and deploying leaders into public office. Despite the increasing role of elections in the choice of leaders by the people of the continent, the continent has also experienced a spike in unconstitutional changes of governments through coups, which poses a significant threat to democratic governance and the rule of law. Notable coups have taken place in what is now being identified as the Africa coup belt with Gabon, Niger, Burkina Faso, Sudan, Guinea, Chad and Mali experiencing successful and even somewhat popular coups. Some of the countries where coups took place had undergone elections making researchers and analysts conclude that people have lost confidence in institutions set up to strengthen and defend democracy. Fraudulent elections have been deemed to constitute constitutional coups owing to instrumentalising the electoral process as a vehicle for power acquisition or retention.

Challenges and opportunities in Africa’s Super Election Year.

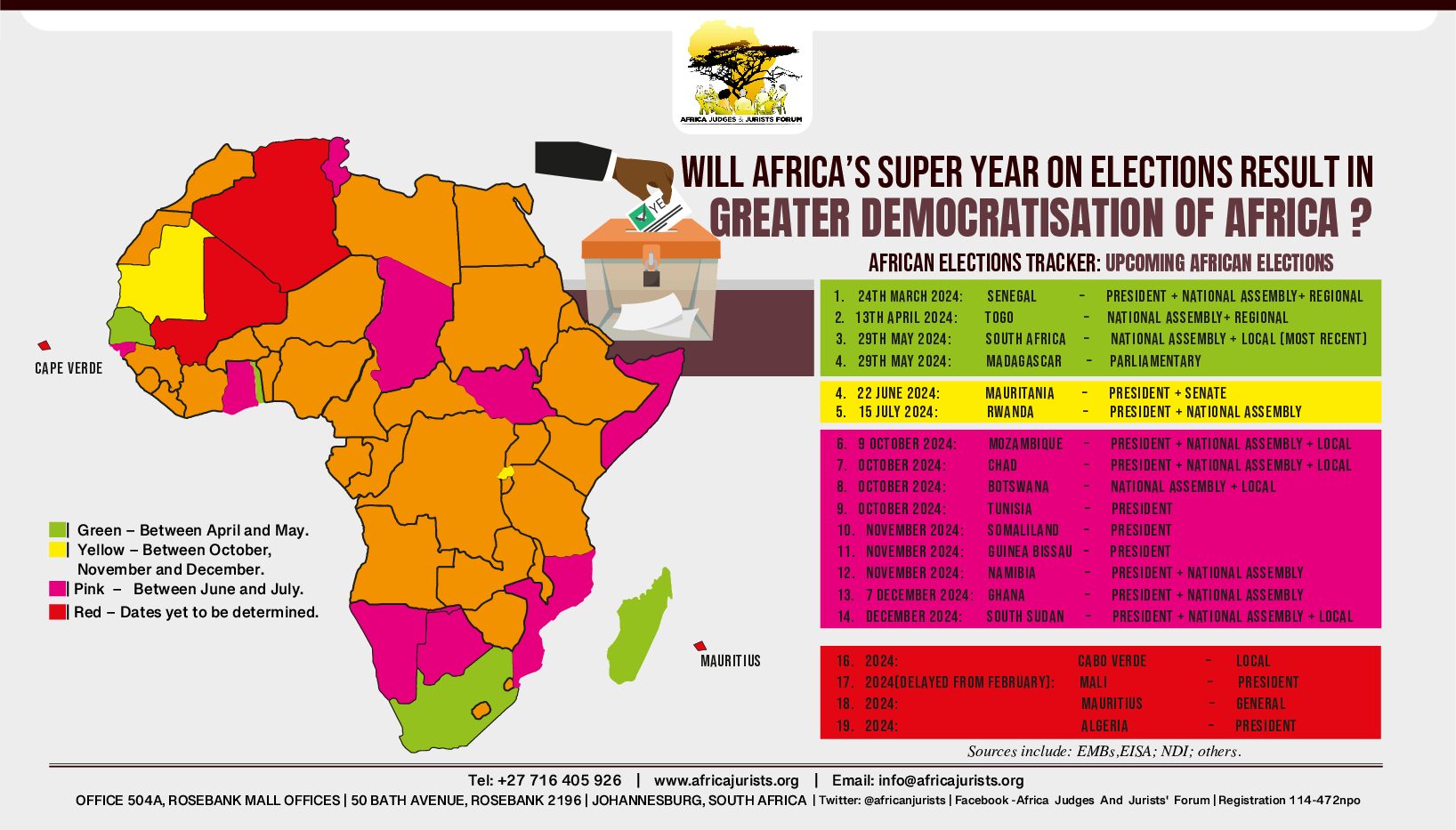

The UNDP has identified 2024 as “a hugely significant elections year” given that over 2 billion people in 72 countries in the world “will have the chance to vote, far more in one year than ever before.” 19 of those elections are expected to take place in Africa. No wonder why 2024 has earned the identity of an election super year! Senegal has already held elections in March 2024 after initial attempts by the incumbent President Macky Sall to postpone the elections to December 2024 that resulted in widespread protests by Senegalese demanding that the elections be held as constitutionally mandated. South Africa is next to hold elections in May 2024 making the beginning of the super elections year in Africa to start with arguably the most developed democracies on the continent. A significant number of Africa’s 19 elections in 2024 are concentrated in the final quarter of the year. The countries that are expected to hold elections in the Elections Super Year 2024 are the following, Senegal, Togo, South Africa, Madagascar, Mauritania, Rwanda, Mozambique, Chad, Botswana, Tunisia, Somaliland, Guinea Bissau, Namibia, Ghana, South Sudan, Cape Verde, Mali, Mauritius and Algeria.

South Africa’s elections highly anticipated

South Africa’s elections are heavily anticipated. South Africa has had a history of the liberation party, the African National Congress (ANC) winning elections in the past without major challenges and without the need to form a coalition central government. This has been a consistent pattern in several Southern African countries such as Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Namibia, Botswana, Tanzania and Angola where single-party dominance of the liberation struggle parties has been the norm for years. With sustained intra-party polarisation and toxicity, and the inability in the past to create conditions for the majority of poor people to have meaningful economic activity, many people believe that the ANC faces one of its toughest elections and runs a real risk of being unable to earn more than a fifty percent majority. This may force the ANC to get into a coalition arrangement to form central government, which, if it happens will be a first since 1994 when apartheid ended. This potential shift in South Africa may signal a phase in Southern Africa of evolution of multiparty politics and see the rest of the sub-region emulate developments in Zambia and Malawi where there has been peaceful transition of power from the ruling/governing parties including liberation movements, following democratic elections.

Elections in the Coup belt of Africa

Outside of Southern Africa, several Sahelian countries that have experienced coups in recent times are on track to hold elections as part of their agreed-upon timetable to return to civilian rule. The seeming popularity of coups in Africa has been vexing. Questions have been asked if the people of Africa prefer military as opposed to democratic rule. Surveys conducted by the Afrobarometer in 39 countries “reveal that many African citizens support military intervention – but also that most societies do not want army rule, and see coups as a short-term solution to a crisis of democracy. In the latest round of surveys conducted over the last two years, a slight majority (53%) say that they support armed intervention if civilian leaders abuse power. Yet a much larger majority (68%) say they are against military government. Afrobarometer conclude therefore that military coups show loss of confidence in institutions of democracy. This therefore emphasis the importance of African states holding elections that are free, fair and credible. The outcomes of elections in the coup belt of Africa will significantly influence the governance trajectory of the region and its response to growing security challenges. =

Senegal elections as a victory for democracy in Africa

The developments that happened in Senegal as a leading democratic state in West Africa and the ECOWAS region which is also seen as the Coup belt of Africa are key. When President Macky Sall tried to postpone the elections from February 2024 to December 2024 in order to give time to his preferred candidate to gain ground ahead of elections, many characterised this as a constitutional coup. Senegal had joined the coup nations of West Africa and the Sahel region, away from its image as a model of democracy. This was particularly sad given that Senegal had consolidated its position not just as a democracy, but a democracy enforcer, when it defended the votes of the people of The Gambia after the authoritarian leader Yayah Jameh had tried to retain power despite losing an election. Thankfully, the Judiciary of Senegal intervened, overturned the President’s decision to postpone elections and ordered that the elections be held within the constitutionally mandated timeframe. Elections were consequently held in March 2024. Senegal reaffirmed its position as a leading constitutional democracy in West Africa with peaceful transition of power from a ruling/governing party to an opposition party at the presidency level following democratic elections. It is hoped that the rest of West African and Sahel nations, especially in the coup belt will emulate this development in Senegal and put Africa back on a path of sustainable democratisation and away from the legacies of military rule, whether direct or indirect.

Senegal and Importance of Robust Election Dispute Resolution

When president Macky Sall postponed elections. Senegal was thrust into potential conflict with violent demonstrations taking place. A remarkable thing happened that the key stakeholders in Senegal remained with confidence and faith in the ability of the judiciary to intervene to resolve electoral disputes. A number of countries in Africa have had opposition parties that have chosen not to subject electoral disputes to judicial electoral dispute resolution ostensibly because of losing confidence in the independence of the judiciary. In West Africa Sierra Leone is one of them. The intervention of the judiciary in Senegal helped to prevent potential pro-longed conflict in Senegal, as well as the dangers of a government whose legitimacy is questioned, remaining in power to the detriment of sustainable peace and development of the country. Elections are a threat multiplier to judicial independence, yet judicial independence guarantees that election stakeholders can resort to the courts when faced with significant disagreements and conflict in the election cycle.

Obstacles to free and fair elections in Africa

Some of the issues that will characterise or need navigation in the 2024 super election year in Africa include tackling the notion or mode of power as an end in itself and therefore at any cost. With this operating mode, elections become a mere instrument to acquire and retain power. Elections are orchestrated exercises and not genuinely competitive processes. The focus is on outcome certainty as opposed to procedural certainty. Outcome certainty is a situation where those who organise elections do so with a clear winner in mind. With a focus on the certainty of the outcome, election legal framework and procedures are made to be vague, EMBs do not set up a clear election calendar, civic space is made toxic and dangerous for voters and other key election stakeholders such as opposition and pro-democracy activists. There is no incentive created to encourage civic participation and engagement in governance. The new emerging threat that will continue to escalate is information pollution before, during and after elections driven by AI generated information that is disseminated through social media. Failing to address these issues risks further diminishing the standards of electoral integrity in Africa and creating conditions fertile for military coups.

The Rise of Information Disorder in African Elections.

A new phenomenon worth sustained monitoring in the election super year is the increasing power of social media and artificial intelligence to pollute the information environment that has made information disorder a key election stakeholder in elections in the Africa super year on elections and at a scale never seen before. In many countries where elections are heavily contested and sometimes the environment is toxic and polarised, generative AI and social media are used to fan hate messages and to create severe information pollution. Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) results in the use of 4 Vs to try and capture the political market or influence the elections to produce certain outcomes that may not be democratic. The 4 Vs are Volume, Velocity, Virality and Verisimilitude. GAI results in information being produced in large Volumes. The use of ICT and social media results in information generated to move at great Velocity. With GAI the large volumes of information are moved at high velocity to a micro-targeted audience to produce Virality. The use of GAI and machines that learn and make human-like decisions also results in content production that looks credible and very difficult to identify and distinguish as fake, especially deep fake videos in elections, hence the quality of Verisimilitude. National authorities and EMBs have not yet adopted legal and policy frameworks to regulate the information market effectively in a way that protects fundamental rights of the electorate. Election observers have not yet developed tools to effectively monitor the impact of information disorder on the right and ability of voters to make informed decisions and choices that is a prerequisite of free, fair and credible elections

Myths and Realities about African Elections:

Throughout the decades the concept of democratisation through elections has been a central tenet of Africa’s political landscape. Yet, as the continent navigates its journey towards democratic governance, the question arises: is this notion merely a myth, or is it a tangible reality?

Elections as a Facade: Critics argue that elections in Africa often serve as a mere facade, offering the illusion of democracy while preserving authoritarian rule. These elections, they contend, are marred by irregularities, voter intimidation, and manipulation, rendering them far from free and fair. The recent history of rigged elections and power consolidation by incumbents in various African countries provides ample fodder for this argument.

Elections as Seeds of Change: Amidst the scepticism lies a profound reality: elections have undeniably planted the seeds of change across the African continent. Take, for instance, the case of Nigeria, where the transition from military rule to civilian democracy in 1999 marked a significant milestone. Despite ongoing challenges, Nigeria has witnessed multiple peaceful transitions of power through elections, demonstrating the potential for democratic progress.

One- or Two Party Dominance: Another argument against the democratisation narrative is the prevalence of one-party dominance in many African nations. Critics point to countries like South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zimbabwe and Angola, where ruling parties have maintained a stranglehold on power for decades. They argue that elections are a tool for perpetuating one party rule. Others counter this argument by giving examples of the USA and the UK which are viewed as mature democracies but where there are two parties that have historically exchanged power between them using the electoral process. The argument is that entrenched political monopoly undermines the very essence of multiparty democracy.

Emergence of Alternatives: Yet, even in the face of one-party dominance, Africa has seen the emergence of alternative voices and movements challenging the status quo. The recent political upheavals in countries like Sudan and Ethiopia illustrate the power of popular movements in demanding political reform and accountability. These movements, driven by a desire for genuine democracy, offer a glimmer of hope that authoritarian rule will continue to face bottom up pressure from the electorate.

Coup Culture: A prevalent myth surrounding democratisation in Africa is the persistence of the “coup culture,” where military interventions disrupt democratic processes and undermine stability. The coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Guinea in the recent past serve as stark reminders of this enduring challenge, casting doubt on the feasibility of democratic consolidation.

Resilience of Institutions: However, Africa’s democratic journey is not defined solely by coups and setbacks. The continent has witnessed the resilience of democratic institutions in the face of adversity. Take, for instance, Kenya, often hailed as the beacon of Democracy Africa. Despite experiencing violent elections in 2007 and several other elections before and after that, Kenya has established robust electoral mechanisms, judicial system and a vibrant civil society, demonstrating the capacity for democratic resilience, and so is the same with Senegal and Ghana which are beacons of Democracy in West Africa.

Conclusion

In Conclusion, the question remains whether Africa is undergoing democracy consolidation or democracy decay or regression? 2024 as an elections super year will help us try to answer this question. Time will tell but it is important for election practitioners to observe developments during this election super year in Africa and draw lessons to improve electoral practices. While challenges persist, from electoral fraud, the impact of information pollution, to authoritarian rule, there is also evidence of incremental progress. As Africans continue to strive for democratic governance, let us confront the myths, embrace the realities, and work towards a future where democracy thrives for all. A common thread running through African countries is the strong desire among citizens and the people of Africa to have their voices heard. This underscores Africa’s collective aspiration for more accountable, citizen-centric, and democratic governance.

About the Authors;

Arnold Tsunga is a human rights lawyer and the Managing Partner at Tsunga Law International. Arnold is the Rule of Law and Elections Expert at Africa Judges and Jurists Forum.